Jennifer M. Chen, Karin E. Schütz, and Cassandra B. Tucker Department of Animal Science, University of California, Davis 95616 AgResearch Ltd., Hamilton 3240, New Zealand

Dairies in the United States commonly cool cattlewith sprinklers mounted over the feed bunk that intermittently spray the cows’ backs. These systems usepotable water—an increasingly scarce resource—butthere is little experimental evidence about how muchis needed to cool cows or about droplet size, whichis thought to affect hair coat penetration. Our objectives were to determine how sprinkler flow rate anddroplet size affect physiological measures of heat loadin a hot, dry climate, and to evaluate cooling effectiveness against water use. The treatments were anunsprayed control and 6 soaker nozzles that deliveredfour 3-min spray applications of 0.4, 1.3, or ≥4.5 L/min (with 2 droplet sizes within each flow rate) andresulting in 30 to 47% of spray directly wetting eachcow. Data were collected from high-producing lactating Holsteins (n = 19) tested individually in ambientconditions (air temperature = 31.2 ± 3.8°C, mean ±standard deviation). Cows were restrained in headlocksfor 1 h and received 1 treatment/d for 3 d each, withorder of exposure balanced in a crossover design. Whencows were not sprayed, physiological measures of heatload increased during the 1-h treatment. All measuresresponded rapidly to spray: skin temperature decreasedduring the first water application, and respirationrate and body temperature did so before the second.Droplet size had no effect on cooling, but flow rateaffected several measures. At the end of 1 h, 0.4 L/min resulted in lower respiration rate and skin temperature on directly sprayed body parts relative to thecontrol but not baseline values, and body temperatureincreased to 0.2°C above baseline. When 1.3 or ≥4.5 L/min was applied, respiration rate was lower than thecontrol and decreased relative to baseline, and bodytemperature stayed below baseline for at least 30 minafter treatment ended. The treatment that best balanced cooling effectiveness against water usage was 1.3L/min: although ≥4.5 L/min reduced respiration raterelative to baseline by 4 more breaths/min than 1.3 L/min did (−13 vs. −9 breaths/min, respectively), eachadditional liter of water decreased this measure by only≤0.1 breaths/min (≤1% of the total reduction achievedusing 1.3 L/min). We found similar water efficiencypatterns for skin temperature and the amount of timethat body temperature remained below baseline aftertreatment ended. Thus, when using this intermittentspray schedule in a hot, dry climate, applying at least1.3 L/min improved cooling, but above this, additionalphysiological benefits were relatively minor.

Weather conditions such as high air temperature andexposure to solar radiation cause cattle to gain heat. Cows dissipate heat through evaporation by increasing respiration rate, panting, and, to a limited extent,sweating (Gebremedhin et al., 2008). However, whenthis is insufficient, the accumulated heat load canincrease body temperature and decrease milk yield(Wheelock et al., 2010) and fertility (De Rensis andScaramuzzi, 2003) and, in extreme cases, can result inmortality (Stull et al., 2008; Vitali et al., 2009).

To manage heat load, dairy producers provide shade,fans, spray cooling (sprinklers/soakers with large droplets, or misters with fine droplets), or a combinationof these resources: 94% of US dairies use at least oneof these types of heat abatement (USDA, 2010). Spraycooling, typically provided either in the holding pen orat the feed bunk, is common (62% of milking herds ≥500head; USDA, 2010) because it lowers body temperatureand respiration rate (Valtorta and Gallardo, 2004; Kendall et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2013) and improvesfeed intake and milk yield in hot conditions (Keister etal., 2002). Although spray cooling is 1 of 3 main usesof potable water, along with drinking water (at least57 to 110 L/d per cow; Kume et al., 2010) and water used for milking (e.g., cleaning cows before milking, milking equipment, and the milking parlor, 170 to 734 L/d per cow; Meyer et al., 2006), the amount of water used for cooling varies widely among farms (e.g., 23 to 256 L/d per cow; G. Tresoldi, University of CaliforniaDavis; personal communication). Along with increasing global temperatures, decreasing precipitation or changes in precipitation patterns are predicted to limit water availability (Rosenstock et al., 2006). Therefore, the ability to reduce heat load in cattle while reducing water consumption is an important issue for US dairy production.

There is little evidence for how much water is needed to effectively cool cows. Spray reduces heat load through evaporation when the water is turned off, as well as by cooling the microclimate around the cow. Some heat may be dissipated through fluid convection when water drips from the body but this is associated with speculative concerns about mastitis (e.g., as suggested by Flamenbaum et al., 1986). To determine how much water is needed to cool via evaporation, Arkin et al. (1991) estimated the evaporative potential of a wet, excised hide (≤0.23 L/m2 ), and heat transfer models have been created for different ambient conditions (Kimmel et al., 1991; Gebremedhin and Wu, 2002). However, there has been little experimental validation on live cows, and comparing cooling effectiveness across studies is challenging, as some do not report how much water is used (Araki et al., 1985; Igono et al., 1987; Valtorta and Gallardo, 2004), or use variable units of measure: most commonly liters per minute (e.g., Chen et al., 2013) or liters per hour (e.g., Gallardo et al., 2005), but also cubic meters per hour (Flamenbaum et al., 1986), millimeters per centimeter squared per hour (Granzin, 2006), milliliters per meter squared per minute (Schütz et al., 2011), or millimeters per hour (Kendall et al., 2007). The only study to date that directly compared sprinkler flow rates (mounted over the freestalls and without unsprayed controls) found no differences in heat load when spraying 5.2, 8.2, or 11.7 L/min in 1.5- min applications in a hot, humid climate (Means et al., 1992). It seems likely that effective cooling can beachieved with less water than these relatively high flow rates; in a subsequent study that applied 5.2 L/min,Montoya et al. (1995) calculated from runoff that only 15% of the spray applied evaporated directly from thecows.

In addition to the amount of water, spray droplet size may play a role in cooling. Some smaller droplets may evaporate before reaching cattle; although this may cool the microclimate, the resulting increase in relative humidity may also reduce the potential for water to evaporate from the cows. Small droplets can also accumulate on the hair coat, which some have suggested may limit cooling effectiveness (Hahn, 1985; Flamenbaum et al., 1986) or even create an insulating barrier which traps heat (Armstrong, 1994; Mitlöhner et al., 2001). In contrast, larger droplets may be less likely to evaporate before reaching the cow and could better penetrate the hair coat to the skin, improving cooling effectiveness, but this has not been explicitly examined. Our objective was to determine how sprinkler flow rate and droplet size influence physiological signs of heat load in a hot, dry climate and the efficiency of water usage. We predicted that measures of heat load would be lower for higher flow rates and larger dropletsizes (within a given flow rate).

During or following a single 3-min spray application, body temperature, respiration rate, and skin temperature were lower when ≥4.5 L/min was applied relative to an unsprayed control. For all flow rates, we observed lower respiration rate and skin temperature on the directly sprayed body parts by the end of the 1-h intermittent (3 min on, 12 min off) sprinkler treatment compared with the control treatment. However, only sprinklers delivering ≥1.3 L/min resulted in lower body temperature and skin temperature on the legs compared with the control treatment, reduced respiration rate relative to baseline values, and kept body temperature below baseline for at least 30 min after treatment ended.

Physiological Response to Ambient Conditions

All physiological measures increased when ambient conditions were warmer, sunnier, or less humid or windy—a pattern that is observed across the literature. For example, with each 7°C increase in air temperature in our study, baseline respiration rate and body temperature increased by about 19 breaths/min and 0.6°C respectively.

The relationships are similar when comparing across experiments: our average air temperature during testing was at least 7°C higher than that in some other studies (Kendall et al., 2007; Schütz et al., 2011), and our baseline respiration rate and body temperature were also at least 16 breaths/min and 0.4°C higher, respectively. We also found a relationship with shoulder skin temperature that replicated the findings of Schütz et al. (2011): for each 100 W/m2 increase in solar radiation, skin temperature increased by 0.6 and 0.4°C, respectively (note that the authors reported 0.004°C, but this was in error according to K. Schütz). Ambient conditions are also associated with the accumulation of heat load over time: after 1 h without cooling in our study, respiration rate in the control treatment increased by 11 breaths/min and body temperature increased by 0.5°C relative to baseline, whereas these measures increased by only 6 breaths/min and 0.3°C above baseline, respectively, when unsprayed cows were tested for 90 min in cooler conditions (Kendall et al.,2007)

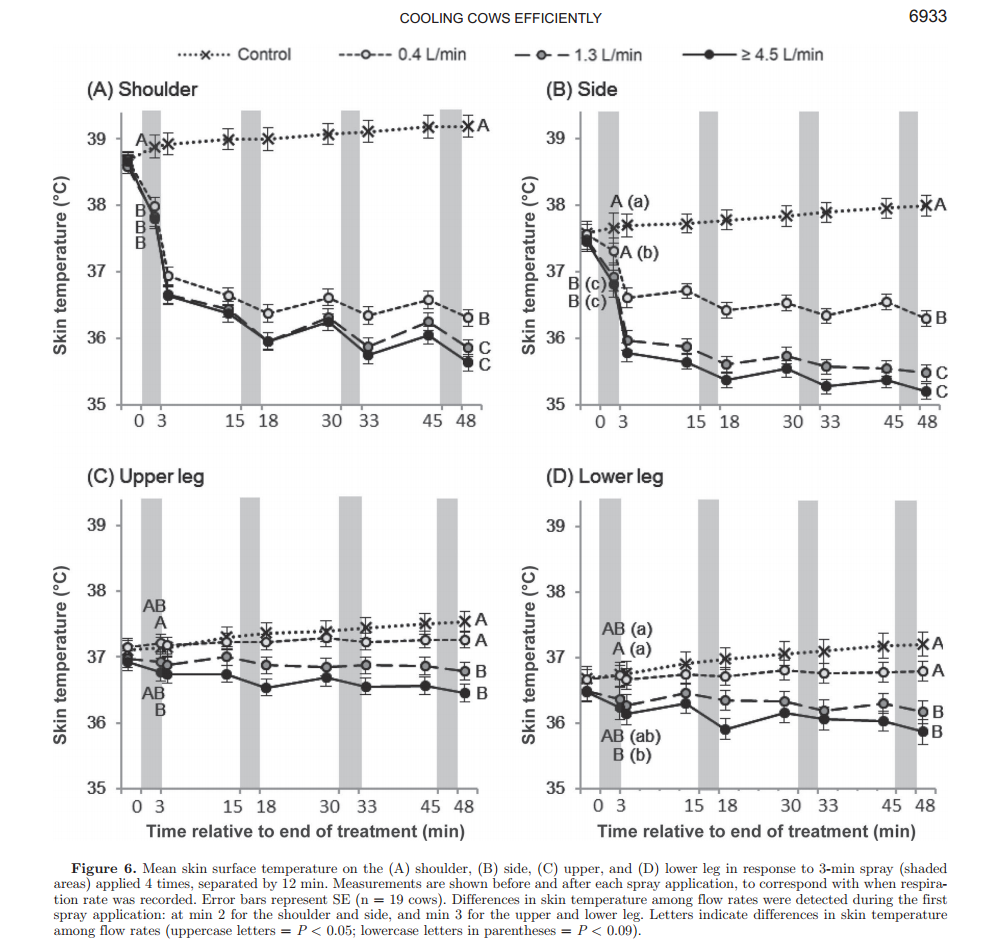

Timing of Physiological Responses to Spray

The timing of when each physiological variable first responded to spray application depended on both the measure and sprinkler flow rate. For skin temperature changes began to occur during the first 3-min spray application: at min 2, all sprinkler flow rates resulted in lower skin temperature relative to the control on the shoulder, and tended to on the side of the body as well; at min 3, ≥4.5 L/min resulted in lower skin temperature than 0.4 L/min on the upper leg, and tended to result in lower values than the control on the lower leg. Ours is the first study to evaluate changes in skin temperature while spray is being applied; others have found this measure to be lower relative to controls after 10 min of spray (Schütz et al., 2011). We also found that immediately following the first spray application, flow rates ≥1.3/min resulted in lower respiration rates relative to the control. Ours is the first study to find changes in this measure after 3 min of spray; others have found it to be lower compared with controls at the end of 90- and 10-min spray applications, respectively (Kendall et al., 2007; Schütz et al., 2011), or after a 20- to 30-min premilking sprinkler treatment (Valtorta and Gallardo, 2004). Finally, we found that body temperature changed before the second spray application: at min 13, ≥4.5 L/min resulted in lower values than the control (and tended to relative to 0.4 L/min as well). Brown-Brandl et al. (2010) found similar timing: when beef heifers were sprayed for ≤30 s with a hose, body temperature was lower than that of controls after approximately 11 min.

Skin Temperature and Heat Flow in the Body

Skin Temperature and Heat Flow in the Body The skin temperature patterns we observed were consistent with predicted heat flow in the body: baseline measurements were lower toward the extremities, decreasing by at least 0.5°C from the torso (shoulderand side) to the upper leg, and by another 0.4°C tothe lower leg. Hernández-Rivera et al. (2011) likewiserecorded lower skin temperature on body parts furtherfrom the core (≤0.2°C lower on the thurl vs. flank),but the opposite pattern has also been reported forthe same locations (Avendaño-Reyes et al., 2012). Sunexposure may affect these measurements: in our study,skin temperature was higher on the shoulder, whichreceived direct sunlight during treatment, comparedwith the side, which was typically shaded by the body.At the end of the 1-h intermittent sprinkler treatment,all flow rates substantially lowered skin temperature onthe shoulder and side relative to both baseline valuesand the control. When Schütz et al. (2011) recordedsurface temperature on the shoulder, this measure was4°C lower for sprayed cows than for controls, similarto the ≥2.9°C difference we found. On directly wettedbody parts, it is possible that skin temperature measurements also reflect water temperature, which was,on average, 8°C and 10°C lower than baseline shouldersurface temperature in our study and that of Schütz etal. (2011), respectively.On the leg, which remained dry, only the higher flowrates affected skin temperature: ≥1.3 L/min resulted inlower values at the end of 1 h compared with the control, and ≥4.5 L/min reduced this measure relative tobaseline as well. Reduced skin temperature on the leg isconsistent with vasoconstriction in response to cooling(Finch, 1986; Osborn et al., 1992), but it is also possible that this change reflected the cooler microclimatesurrounding the cow, also associated with spray (Arakiet al., 1985; Kendall et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2013).Measuring skin temperature by affixing loggers directly onto shaved skin may have affected heat flowcompared with other parts of the body that were covered by hair but not by a logger. Alternative techniquesfor measuring skin or surface temperature have otherchallenges: infrared guns (e.g., Hernández-Rivera etal., 2011; Schütz et al., 2011) and thermography (e.g.,Osborn et al., 1992) are poorly suited for use in directsunlight or on wet surfaces, cows kicked when a thermocouple probe (e.g., Legrand et al., 2011) was appliedto the leg during pilot testing, and subdermal probes(used to assess wound healing in pigs; Cuttle et al.,2010) are more invasive. Rather than using skin temperature to indirectly assess vasodilation and constriction, noninvasive ultrasound has been used to measureblood flow more directly in both beef and dairy cattle(Bollwein et al., 2000; Kirch et al., 2008); this techniquewarrants further exploration for evaluating responses toheat-abatement strategies such as sprinkler

Body Temperature Beyond the End of Treatment

We used 2 approaches to assess how sprinklers affected body temperature in the longer term: for each flowrate, we determined when this measure converged witha contemporary control and also when it returned tobaseline values. Both approaches showed that sprinklerscould continue to cool cows after treatment ended, butyielded different information about the effectiveness ofeach flow rate and timing. When comparing against thecontemporary control, body temperature stayed lowerfor all sprinkler flow rates until converging around 2 hafter treatment. Body temperature ultimately decreased(albeit more gradually in warmer weather) after theend of the control treatment, but increased over timefollowing the sprinkler treatments. These patterns arelikely due to cows in our study having access to shadeafter treatment: relative to no cooling resources, shadealone can reduce body temperature but is less effectivethan sprinklers (e.g., Kendall et al., 2007) Others have similarly found that body temperature remained lower than controls for 1.5 h (Brown-Brandl et al., 2010) or even 2 to 4 h after spraying stopped (Araki et al.,1985; Kendall et al., 2007). Before converging with the control, body temperature in our sprinkler treatments returned to baseline values. This happened sooner for lower flow rates: 8 min after spraying ended when we applied 0.4 L/min, but 32 and 47 min after we used 1.3 and ≥4.5 L/min, respectively. When we applied ≥1.3 L/min, wind extended the duration, similar to when sprinklers are combined with fans (as reviewed by Collier et al., 2006). Others have similarly found body temperature to reach a nadir between 30 and 60 min after spraying stopped (Araki et al., 1985; Flamenbaum et al., 1986; Kendall et al., 2007).

Water Use Efficiency

Because 0.4 L/min cooled less effectively than thehigher flow rates when applied for the same amountof time, we will compare only 1.3 and ≥4.5 L/minwhen discussing the most efficient option. Over thecourse of the 1-h treatment, the 1.3 and ≥4.5 L/minflow rates delivered a total of 15.6 and ≥54.0 L ofwater, respectively, of which about 5.5 and ≥16.4 L,respectively, directly wetted the cows (as estimatedfrom our model of a cow’s back). Overall, 1.3 L/minbalanced cooling effectiveness and water usage mostefficiently. Although ≥4.5 L/min was the only treatment that reduced skin temperature on the upper legrelative to baseline, only relatively minor additionalphysiological benefits were associated with applyingmore than 1.3 L/min. For example, relative to baseline, ≥4.5 L/min lowered respiration rate by 4 morebreaths/min than 1.3 L/min (−13 vs. −9 breaths/min,respectively), but this meant that each additional literof water beyond 15.6 L decreased respiration rate byonly ≤0.1 breaths/min. Similarly, ≥4.5 L/min keptbody temperature below baseline values after the endof treatment for 15 min longer than 1.3 L/min did (47vs. 32 min, respectively), but each additional liter ofwater extended the duration by only ≤23 s. We foundsimilar patterns when evaluating how well each flowrate reduced skin temperature on the side, shoulder,and lower leg relative to baseline, compared againstwater usage. Relative to the control, both flow ratesresulted in lower body temperature and skin temperature on all parts of the body.

When 1.3 L/min was applied for 3 min, the actualvolume that wetted each cow (1.4 L, estimated fromour model of a cow’s back), was similar to guidelinesthat suggest applying 0.9 to 1.3 L/cow per cycle whenspraying intermittently (Brouk et al., 2003, 2005;Washington State University Veterinary MedicineExtension, 2008; Bailey et al., 2012). However, moreresearch is needed to evaluate whether the most efficient amount of water required for cooling cows in ahot, dry climate changes with varying time spent at thefeed bunk, including longer periods that will allow forthe measurement of production responses such as feedintake and milk yield, and also to quantify how flowrate and droplet size influence spray drift (which affectshow much cows and feed are wetted)

Our study provides experimental evidence for howmuch water is needed to efficiently cool lactating dairycows in regions with hot, dry summers. Flow rate,rather than droplet size, was the main determinant ofcooling effectiveness when cattle were restrained for 1 hunder intermittent spray (4 applications of 3 min each).The flow rate that best balanced cooling effectivenessagainst potable water usage was 1.3 L/min (resultingin about 1.4 L/application directly wetting each cow).When at least this amount was used, respiration rateand skin temperature decreased relative to baseline atthe end of the 1-h treatment, and body temperaturestayed below baseline for at least 30 min beyond theend of treatment. Applying additional water did littleto improve cooling effectiveness. Finally, we found thatsprinklers rapidly affect physiological measures of heatload: changes occurred during the first 3-min spray application for skin temperature, at min 4 for respirationrate, and at min 13 for body temperature (before additional spray was applied)