D M GOLHER, P THIRUMURUGAN, B H M PATEL and V K UPADHYAY.

Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Mukteshwar, Uttarakhand 263 138 India

Received: 19 April 2014; Accepted: 23 July 2014

A study was conducted to explore the utility of different drinking water temperature, viz. ambient water

temperature (10.25±0.28°C, T1), 15–20°C (T2) and 35–40°C (T3) during winter at IVRI, Mukteshwar campus on 18 crossbred (HF × Haryana) lactating cows. They were divided into 3 groups of 6 each and various parameters were studied. At open environment maximum temperature, minimum temperature and mean relative humidity were 11.81±0.45, 1.52±0.27°C and 57.43±2.79%, respectively, the corresponding values for microclimate were 16.61±0.36, 6.68±0.61°C and 86.75±0.55%. Average water intake per cow per day was significantly higher in T3 (40.66±0.55) and compared with cows in T1 (38.63±0.42) and T2 (37.53±0.47). Dry matter intake was more for cows in T3. Daily mean milk yield for the cows in T3 (7.56±0.18 litre) was significantly higher than T1 (6.95±0.16 litre) and T2 (7.06±0.17 litre). Milk SNF, protein and total solids percentages were significantly higher for cows consuming warm drinking water in T2 (15–20°C) and in T3 (35–40°C) than cows consumed ambient cool drinking water. Cows in warm drinking water groups showed relatively more gain in body weight compared to cows provided with ambient cool drinking water. It was concluded that the crossbred cows consuming warm water (35–40°C) performed better than the cows consuming comparatively cold water.

Macroclimatic and microclimatic variables: The range of maximum temperature, minimum temperature, relative humidity (RH) morning and RH evening recorded was 3.0 to 16.9°C, –2.60 to 6.80°C, 10–100% and 26–100% respectively. The corresponding values inside the animal shed recorded were 9.0–21.0°C, 0 to 14°C, 73–89% and 54–91% respectively. Temperature humidity index (THI) in the morning and evening varied from 52.12–62.92 and 55.72–70.12 respectively. For all these variables microclimatic changes inside the shed was higher than the outside environment and value differ significantly. This indicated that tail-to-tail tie-barn house at high altitude temperate region conserved the heat and humidity. This was

due to expired air of animals and evaporation of moisture inside the shed. However optimum productivity of cattle occur at an air temperature of 13–18°C and RH of 60–70% (McDowell 1972) and lower critical value of THI was 64 (Igno et al. 1992).

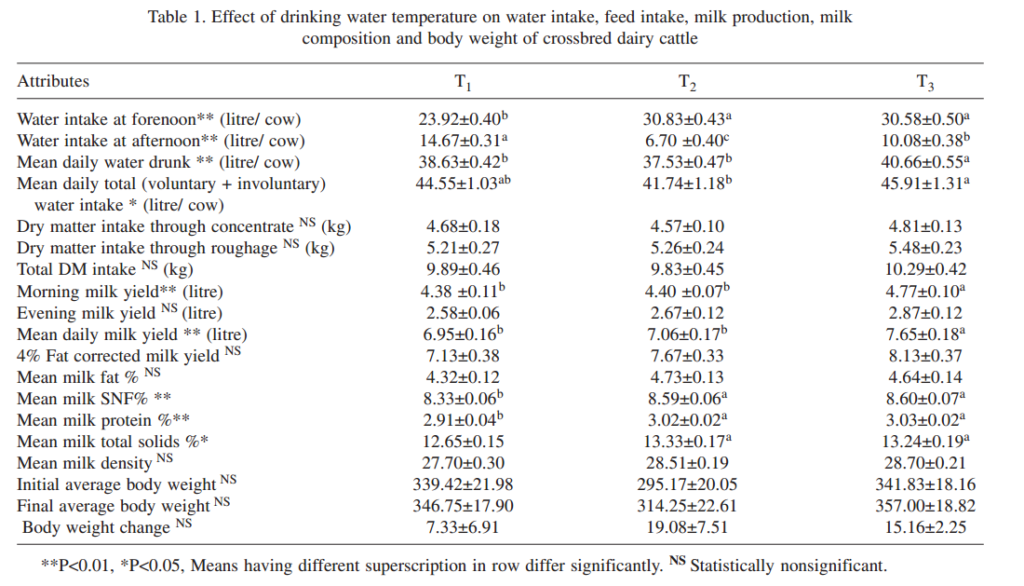

Water and feed intake: Ambient drinking water (T1) temperature during the experiment period recorded at the time of offering to the animals at morning as well as at afternoon and the minimum and maximum temperature of water at morning and afternoon ranged from 2.0–12°C and 3.0–17.0°C. However, overall mean of ambient water temperature (10.25±0.28°C) was 3.59°C higher than the outside air temperature. At morning cows under T3 and T2 drank significantly (P<0.01) more water as compared to T1 (Table 1). This might be due to better palatability of warm water than chill ambient water. Conversely, at afternoon

water intake was differed significantly (P<0.01) among the treatment groups and cows in T1 drank highest quantity of water (14.67±0.31 litres) followed by T3 (10.08±0.38) and cows in T2 drank lowest quantity of water (6.70±0.40 litre). Higher water intake of cows in T1 at afternoon might be due to rise in water temperature compared to morning, which might have increased the palatability. There was a random fluctuation in amount of water drunk in all the 3 treatments with increase in duration of experimental period.

This was possibly due to changes in air temperature humidity and THI during the experimental period. However,average water intake per cow per day was significantly (P<0.01) higher in T3 (40.66±0.55) and compared to cows in T1 (38.63±0.42) and T2 (37.53±0.47), whereas the latter 2 groups’ water intake was statistically comparable. This indicated that water at 35–45°C was more palatable than 15–20°C and lower drinking water temperature. This observation corroborated with reports of Huuskonen et al. (2011) who observed a linear response of water intake to increase in drinking water temperature from near freezing to about body temperature in Holstein cows. Contrarily, Andersson (1985) observed that cows drank significantly (P<0.01) less amount of 24°C water than that of the water at lower temperatures (3, 10 and 17°C). There were statistically significant differences (P<0.05) of total water intake (voluntary + involuntary) among the treatments. Cows under T3 (45.91±1.35), consumed significantly (P<0.05) more water than T2 (41.71±1.18) whereas water intake of cows under T1 (44.55±1.03 litres) was statistically (P>0.05) comparable with those in T3. The higher water intake of cows in T3 might be due to better palatability of warm water (35–40°C) as there was comparable feed intake among the treatment groups. There were no significant differences among different treatment groups in daily DM intake through concentrates, roughages and total DM intake. However DM intake was relatively more for cows in T3. This might be because of increased water intake causing increment in the appetite leading to more milk production. These results are consistent with the findings of earlier worker. At ambient temperature below the lower limit of thermoneutal zone sheep consumed less feed, digest their feed less efficiently and convert more energy to heat production (NRC 1989).

Milk production and its composition: Mean milk yield for morning observed that cows under T3 yielded

significantly (P<0.01) more milk (4.77±0.10) as compared to T2 (4.40±0.07) and T1 (4.38±0.11 litres), whereas the latter 2 groups were statistically comparable and the difference was 0.37 and 0.39 litres higher in T3 group compared to T2 and T1, respectively. However, the differences in milk yield at afternoon hours among the treatment groups were statically comparable. Daily mean milk yield for the cows in T3 (7.56±0.18 litre) was significantly higher than T1 (6.95±0.16 litre) and T2 (7.06±0.17 litre) whereas the differences between T2 and T1 was statistically comparable and the difference was 0.59 and 0.70 litre higher in T3 group. The higher milk yield of cows in T3 group might be due to warm drinking water (35°–40°C) helped in not only conserving the energy but also enhanced the water intake. The cows in T3 group consumed more feed (11.08 ±0.42 kg DM) than the cows in T2 (10.58 ±0.45 kg DM) and cows in T3 (10.89 ±0.46 kg DM). When animals were subjected to extreme cold stress, substantial dietary energy might be diverted from productive functions to the maintenance of body heat (Koknaroglu et al. 2005). The change in metabolic intensity with thermal adaption can be expressed as a 0.91% increase in maintenance energy requirement for each degree below 20°C to which cattle have been adapted (NRC 1981). Johnson (1976) reported that in lactating cows, cold weather and lowered ambient temperatures reduces milk yield. This may be due to the diversion of net energy to the maintenance of body temperature and maintenance than production. Similarly, 4% fat corrected milk (FCM) yield was 1.0 litre and 0.46 litres higher in T3 in comparison to T1 and T2, respectively. This was due to higher milk yield in T3 as compared to T2 and T1 and relatively higher fat percentage in T3 group. The results are in accordance with the previous findings of Osborne et al. (2002). There was no statistically significant difference among the treatment groups for fat percentage of morning as well as evening milk. This might be due to comparable dry matter consumption through roughage among the treatment groups. However, cows consumed warm drinking water in T2 (15–20°C) and T3 (35–40°C) showed relatively higher milk fat percentage than cows consumed cool ambient water. Thompson et al. (1979) concluded that possibly warm drinking water favoured more acetate production in rumen, which in turn increased milk fat percentage. SNF, protein and total solids percentages of milk was significantly higher for cows consuming warm drinking water in T2 (15–20°C) and in T3 (35–40°C) than cows consuming ambient cool drinking water, while the difference in SNF percentage among T2 and T3 was statistically comparable. These results corroborated with the findings of Ozrenk and Inci (2008) and Heck et al. (2009) who reported that changes in protein percentage of cows in cold stress. Mean milk density percentage was statistically comparable for cows consuming warm drinking water in T2 (15–20°C) and in T3 (35–40°C) and cows consuming ambient cool drinking water (T1). The body weights of cows in all the 3 treatment groups were randomly positive and negative energy balance. This might be due to the fact that cows were in different days of lactation and individual cow’s milk yield varied. However cows in warm drinking water groups showed relatively more gain in body weight compared to cows provided with ambient cool drinking water. The lower body weight gain in T1 group might be due to requirement of relatively more energy to maintain the normal body temperature. These results are consistent with Demircan et al. (2007) who reported that cattle raised in cold season had lower average daily gain (ADG) than those in warm season (P<0.05). The results of the experiment revealed that tie-barn house of dairy cattle conserved the heat and humidity during winter at high altitude temperate region. Providing warm drinking water (35–40°C) to crossbred lactating dairy cows during winter at high altitude temperate Himalayan hills improved the acceptance of drinking water as indicated by increased water consumption P<0.05) and increased the average daily milk yield significantly (P<0.05) as compared to cows provided with ambient cold drinking water.